A significant number of Americans are facing challenges in covering their household energy expenses, particularly in the Southern and Southwestern regions. This trend, highlighted in a recent MIT study, indicates a climate-driven transition from heating demands to increased reliance on air conditioning.

The study also unveils that a key U.S. federal program, which distributes energy subsidies through block grants to states, has not adapted adequately to these evolving trends. The researchers assessed the “energy burden” faced by households—a measure indicating the proportion of income spent on energy essentials—between 2015 and 2020. Households with an energy burden exceeding 6 percent of their income are classified as experiencing “energy poverty.” As climate change progresses, the projected rise in temperatures will further strain finances in the South, where air conditioning use is becoming increasingly essential, while milder winter conditions in certain cooler regions may lessen heating expenses.

“Between 2015 and 2020, we observed a general increase in energy burden, with a notable shift toward the South,” explains Christopher Knittel, an MIT energy economist and co-author of the study. He adds, “When we juxtapose the energy burden’s distribution with federal aid allocations, they don’t align effectively.”

The research paper titled “U.S. federal resource allocations are inconsistent with concentrations of energy poverty,” has been published in Science Advances.

The research team comprises Carlos Batlle, a professor at Comillas University in Spain and a senior lecturer in the MIT Energy Initiative; Peter Heller SM ’24, a recent MIT Technology and Policy Program graduate; Knittel, the George P. Shultz Professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management; and Tim Schittekatte, a senior lecturer at MIT Sloan.

Rising Energy Needs in a Warming World

The study stemmed from graduate research conducted by Heller at MIT. Using advanced machine-learning techniques, the researchers analyzed U.S. energy consumption data. They examined a sample of approximately 20,000 households from the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s Residential Energy Consumption Survey, which includes diverse demographic and geographical information.

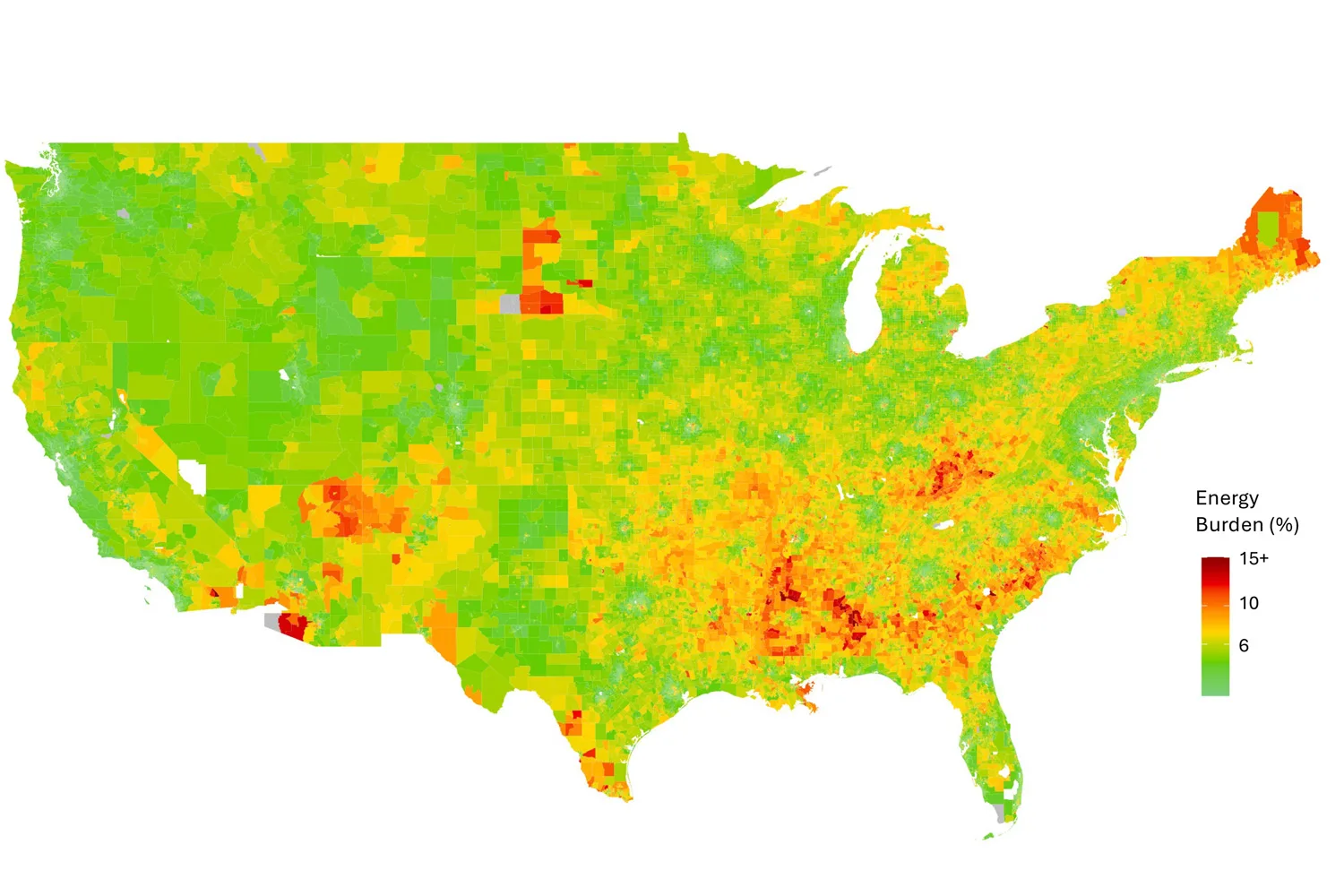

Using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey for the years 2015 and 2020, the authors estimated the average energy burden for every census tract across the contiguous United States—73,057 tracts in 2015, and 84,414 in 2020. This allowed for effective tracking of changes in energy burden, particularly the increasing burden faced by households in southern states.

In 2015, Maine, Mississippi, Arkansas, Vermont, and Alabama had the highest energy burdens, while by 2020, this list shifted, with southern states bearing a larger burden, now including Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama, West Virginia, and Maine. Additionally, there was a noticeable urban-to-rural transition; 23 percent of census tracts categorized as energy-poor were urban in 2015, compared to only 14 percent in 2020.

The findings reflect a warming world where temperate winters in various northern regions require less heating, yet extreme summer temperatures in the South necessitate increased air conditioning. “Who will suffer the most from climate change?” ponders Knittel. “It’s primarily the southern U.S. that faces the greatest challenges, and our research confirms that while energy burdens are increasing, these areas are the least equipped to cope.”

Reevaluating LIHEAP Funding

Beyond merely highlighting the shift in energy requirements over the past decade, the study also traces a longer-term change in U.S. household energy needs dating back to the 1980s. The authors examined the present-day geography of energy burden in relation to support provided by the federal Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), established in 1981.

While federal energy aid predates LIHEAP, the current structure, introduced in 1981 and revised in 1984 to incorporate cooling needs, relies on formulas that often reflect outdated data. For instance, the 1984 changes included “hold harmless” clauses that guaranteed minimum funding for states. However, according to the recent study, LIHEAP allocates a disproportionately smaller share of its funding to southern and southwestern states in light of current energy poverty patterns.

Heller notes, “Congress’s formulaic approach, rooted in the 1980s, results in a funding distribution that remains relatively unchanged.” The research indicates that to eradicate energy poverty entirely in the U.S., LIHEAP funding would need to increase fourfold. Nonetheless, the team proposed a new funding model prioritizing the most in-need households nationwide, ensuring energy burdens remain below 20.3 percent.

“We believe this would be the fairest way to distribute funds, allowing each state to receive sufficient support without any being disproportionately harmed,” suggests Knittel. Implementing this new funding strategy will require some reallocation among states, all aimed at helping households avoid energy poverty, especially during a time of shifting climate dynamics and energy demands across the country.

“Optimizing our funding allocation is essential,” Knittel emphasizes, highlighting the importance of strategic financial investment during these changing times.

Photo credit & article inspired by: Massachusetts Institute of Technology