Does the United States hold a “moral obligation” to assist developing nations that contribute much less to carbon emissions yet suffer disproportionately from climate disasters?

A recent study published in Climatic Change on December 11 delves into American public sentiment regarding international climate policies, particularly against the backdrop of the U.S.’s historical role as a top carbon emitter. This experimental survey specifically assesses Americans’ perceptions of their nation’s moral responsibility.

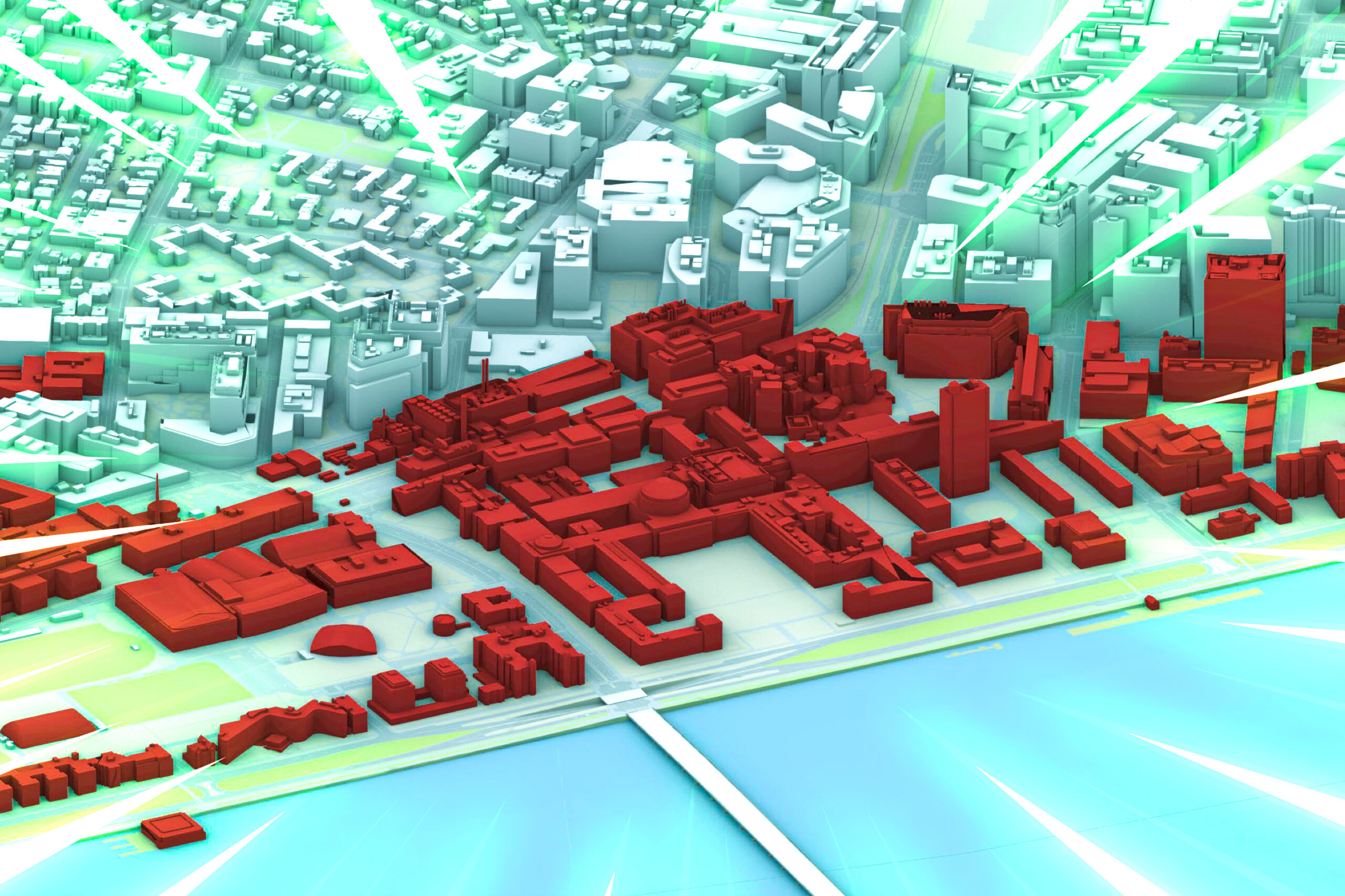

The research team comprised MIT Professor Evan Lieberman, director of the MIT Center for International Studies and Total Chair on Contemporary African Politics, along with Ford Career Development Associate Professor of Political Science Volha Charnysh, political science PhD student Jared Kalow, and University of Pennsylvania postdoc Erin Walk PhD ’24. In this interview, Lieberman shares insights from their findings and presents suggestions for improving climate advocacy efforts.

Q: What were the primary findings and any unexpected results from your study on U.S. climate attitudes?

A: A central topic at the COP29 Climate talks in Baku, Azerbaijan, was: Who will fund the trillions needed to assist lower-income countries in adapting to climate change? While there’s a growing consensus that wealthier nations should bear these costs, commitments often fall short. In the U.S., public opinion on such international aid weighs heavily on politicians as citizens remain focused on local issues.

Prime Minister Gaston Browne of Antigua and Barbuda articulated the viewpoint shared by many leaders, stating that rich nations often perceive climate finance merely as “a random act of charity” rather than acknowledging their moral duties — especially those historically responsible for high emissions.

Our study aimed to gauge American attitudes towards climate-related foreign aid specifically by examining the impact of a moral responsibility narrative. We employed an experimental design, where participants received various messages.

One effective message, framed around “climate justice,” asserted that Americans should aid poorer nations due to the U.S.’s significant role in greenhouse gas emissions. This narrative notably increased support for foreign aid directed at climate adaptation in developing countries. Interestingly, however, we found that the positive impact was predominantly felt among Democrats, with Republicans showing negligible shifts in opinion.

Surprisingly, a message focusing on the idea of collective responsibility — “we are all in this together” — had no overall effect on either Democrat or Republican sentiments.

Q: What are your recommendations for shifting U.S. attitudes towards global climate policies?

A: Our research indicates that in limited budget scenarios, leveraging messages that incorporate elements of blame or shame is more compelling than broader appeals to shared responsibility.

Moreover, targeting communication strategies specifically towards Republicans is crucial, as they demonstrate significantly less support for climate aid. Even among this group, messaging that resonates with Democrats has inconsistent reception. Engaging younger Republicans might also yield more favorable responses to climate initiatives.

Q: With the potential for a new Trump administration, what challenges or opportunities might arise in gaining U.S. public support for international climate negotiations?

A: Trump’s previous withdrawal from the Paris Agreement showcased a clear disdain for international climate initiatives, and his intent to maintain these policies during a potential second term could threaten public support for aiding the world’s poorest nations facing climate impacts. This solid alignment of Republican public opinion with these views leaves little room for optimism.

Individuals concerned about climate impacts should consider supporting state-level, non-profit, and corporate initiatives to advance climate justice.

Q: What final thoughts would you like to share?

A: Those engaged in climate advocacy must reconsider how they communicate the urgent challenges we face. As of now, any mention of “climate change” tends to be dismissed by Republican leaders and segments of American society. Exploring different messaging strategies could identify effective approaches tailored to various audiences.

Our study, alongside other research, highlights that partisan identity is a major factor influencing attitudes toward climate aid, with party affiliation overshadowing the modest effects of climate justice messaging. Just as Republican leaders were once persuaded to take action on global health issues like HIV/AIDS, a similar call to action is needed for climate aid.

Photo credit & article inspired by: Massachusetts Institute of Technology