In an exciting new endeavor, MIT has launched a course this spring that challenges students to envision the essentials for comfortable human habitation in outer space. With NASA’s Artemis program paving the way for long-term moon missions, the time for innovative designs has arrived. Unlike the Apollo missions that merely landed astronauts on the moon, Artemis aims to establish bases both in lunar orbit and on the moon’s surface.

The hands-on, cross-disciplinary design course MAS.S66/4.154/16.89, known as Space Architectures, was developed in collaboration with MIT’s Architecture and Aeronautics and Astronautics (AeroAstro) departments, as well as the MIT Media Lab’s Space Exploration Initiatives group. This spring, thirty-five motivated students from various academic backgrounds came together to brainstorm, design, prototype, and test the necessary components for sustaining human life and activity on the lunar surface.

The course’s popularity reflects a growing interest in space among MIT students. As Jeffrey Hoffman, a former NASA astronaut and current AeroAstro professor, notes, a significant number of students aspire to be astronauts. “Many at MIT are deeply inspired by the idea of living in space, making this course a unique opportunity to explore real design concepts for future lunar habitats,” he explains.

MIT’s historical connection with NASA, particularly during the Apollo era, cannot be overstated. MIT was awarded the first significant contract for the Apollo program in 1961. Dava Newman, the director of the MIT Media Lab and a former deputy administrator at NASA, also contributed as an instructor for this course.

The primary objective of the course is to prepare students for the next phase of human space exploration. With the Artemis missions on the horizon and the increasing prominence of commercial spaceflight, investigating viable habitat designs is more crucial than ever. “At MIT Architecture, we excel when research intersects with practical application,” states Nicholas de Monchaux, a course instructor and head of the architecture department. “As designers are increasingly called upon to create solutions for extreme environments—including space—this is a vital frontier for research and collaboration.”

Designing Lunar Habitats

The course highlights a unique fusion of design perspectives, blending students from architecture with those from engineering. Collaborative activities, guest lectures, and a week-long exploration of NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, the SpaceX launch site in Brownsville, and ICON’s 3D printing facilities in Austin, equipped students for tackling the challenges of designing for space.

Hoffman paints a stark picture of life in space: “It’s one of the most inhospitable environments imaginable. When you’re gazing out the spacecraft window, you know that just beyond it lies a place where survival is impossible.”

The students formed seven teams, and the need for collaboration quickly became evident. During initial phases, differences between architects—who prioritized comfort and livability—and engineers—who considered extreme environmental challenges—often led to conflicts, but these discussions played a fundamental role in developing innovative solutions.

Several teams proposed inflatable designs, including a modular science library for up to four individuals, a rapid-deployment inflatable habitat for short-term lunar shelter, and a semi-permanent structure intended for future moon exploration.

Finding a Common Language

“Architects and engineers typically have varying approaches to design,” notes Annika Thomas, a mechanical engineering doctoral candidate on the MoonBRICCS team. “While integrating our ideas was challenging initially, we gradually developed a shared understanding and coordinated our efforts toward a common project vision.”

Teammate Juan Daniel Hurtado Salazar, an architecture student, points out that engineering considerations often surface late in architectural design processes. “Engineering insights prompted us to confront design implications from the start, fostering discussions about the sacrifices made for optimal resource efficiency in varying contexts,” he states. “As we explored long-term habitats, we had to address the multifaceted needs of astronauts—social, emotional, and practical.”

Kaicheng Zhuang, another architecture graduate involved in the Lunar Sandbags project, emphasizes that clear communication was vital among team members. “Working with engineers necessitated focus on tangible solutions while addressing technical feasibility and structural integrity,” he explains. “Our architecture discussions revolved around the aesthetic, spatial, and user-experience aspects.”

Molly Johnson, an AeroAstro graduate student on the lunarNOMAD project, agrees, noting, “For systems engineers, it’s tempting to overlook minor details, but the architects’ focus on specifics clarified our project goals.”

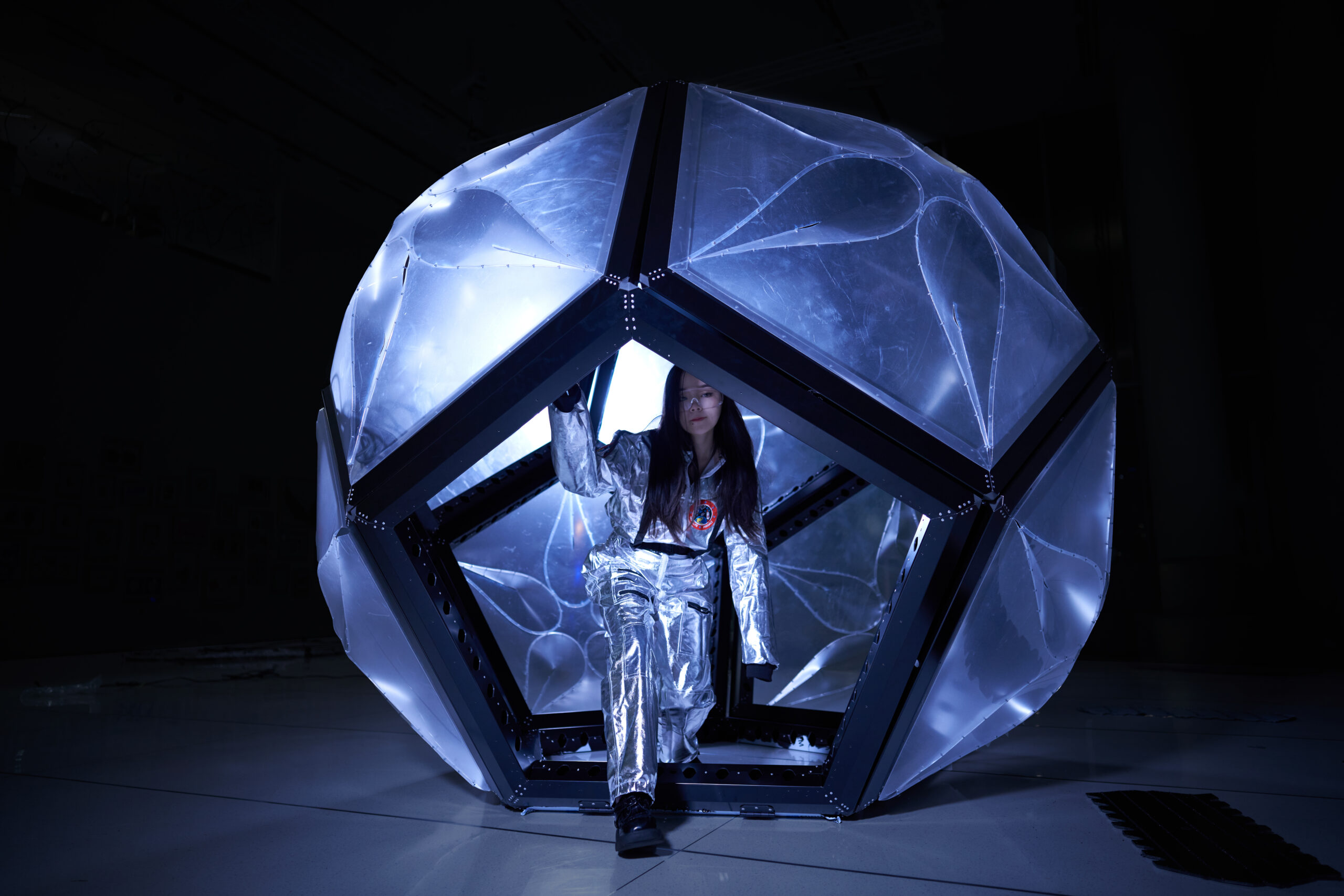

The Momo: a Self-Assembling Lunar Habitat team created a flexible design for a semi-permanent habitat intended for lunar exploration, capable of being compacted for easier transportation. Their innovative structure was recently highlighted in DesignBoom.

Beyond Earth

The diversity of final projects underscored the various approaches taken by teams, despite the limited strategies available for life-supporting structures on the moon. Cody Paige, director of Space Exploration Initiatives, describes how students had to consider material transport, assembly logistics, durability, and the social dynamics of their proposed environments.

Hands-on experience was instrumental in this course, especially in an era where artificial intelligence is intruding into many decision-making processes. Paige articulates the importance of physical prototyping: “Understanding materials’ real-world implications is crucial, as AI may not always capture the nuances of reality. Engaging with these materials firsthand provides invaluable insight.”

While some design concepts may seem fantastical, they could become practical realities soon, especially as industry demand for architects capable of creating habitats for harsh environments grows. “We need to nurture students who will be pioneers of this emerging field,” says Skylar Tibbits, an architecture professor and course instructor. “The longer astronauts spend in space or on the moon, the more imperative it becomes to design habitats that are not only functional but also enhance the human experience.”

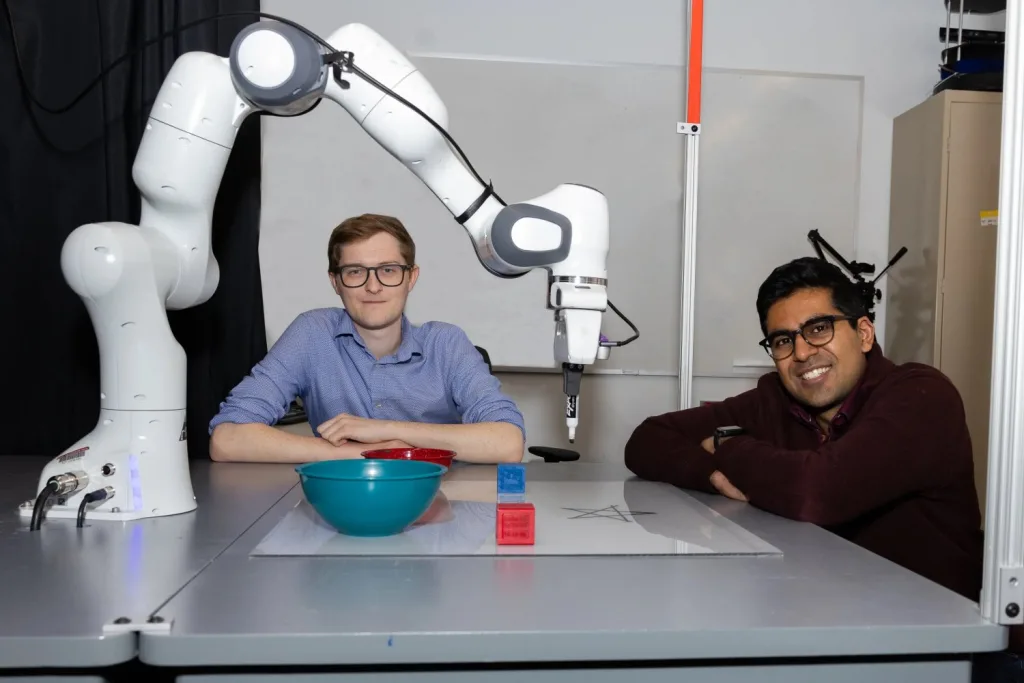

As interest in space architecture continues to rise, the need for skilled architects and engineers in this burgeoning field is evident. Thomas, from the MoonBRICCS team, works on robotics for space applications, while team member Palak Patel studies materials designed for extreme environments. The enthusiasm among students and the persistent demand for such expertise suggest that the course will continue to thrive and evolve.

“We envision transforming this course into a multi-year program focusing on extreme environments, both on Earth and in space. Conversations about sponsorships and partnerships are already underway,” says de Monchaux.

Photo credit & article inspired by: Massachusetts Institute of Technology