Drone shows are rapidly gaining traction as a captivating form of large-scale light displays, captivating audiences with hundreds or even thousands of drones taking to the sky. These drones are meticulously programmed to follow specific trajectories, creating breathtaking patterns in the night sky. However, instances of malfunctioning drones—like those witnessed recently in Florida and New York—pose significant dangers to onlookers, underscoring the critical need for enhanced safety measures.

Such drone mishaps bring to light the complexities involved in ensuring safety within what engineers refer to as “multiagent systems.” These are systems consisting of various coordinated and autonomous agents, including drones, robots, and self-driving vehicles.

Recently, a team of MIT engineers has pioneered a groundbreaking training approach for multiagent systems, ensuring their safe operation even in crowded environments. Their innovative method allows safety protocols learned by a small group of agents to be scaled effortlessly to larger groups, thereby protecting the entire system.

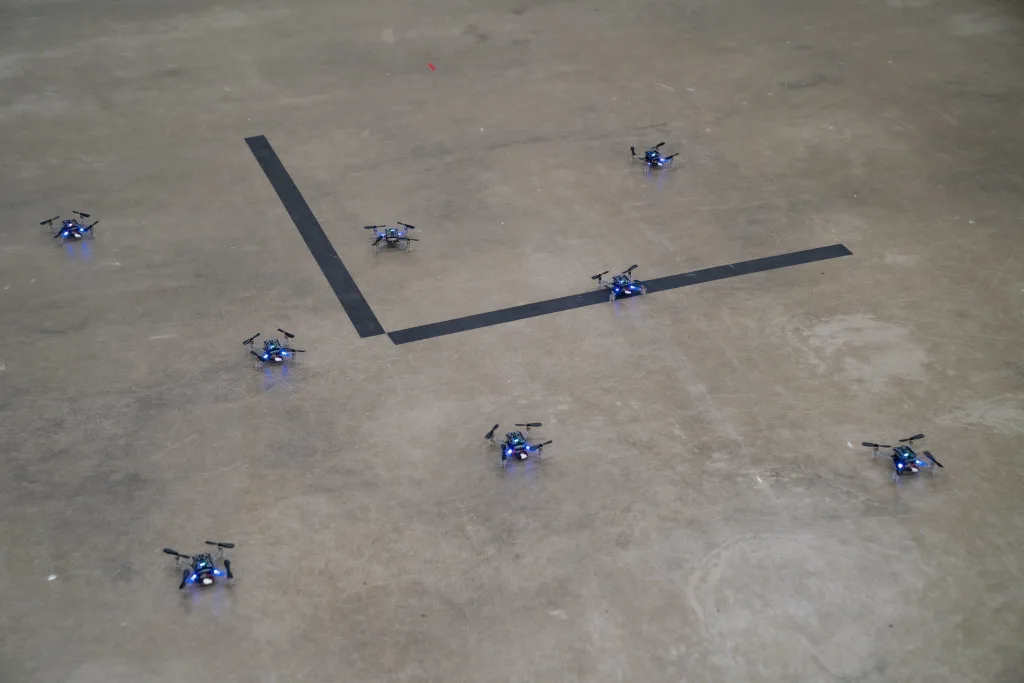

In practical applications, the team trained a handful of small drones to perform a variety of tasks, including mid-air position-switching and landing on moving vehicles. Their simulations demonstrated that programs trained on a limited number of drones could be replicated and scaled up to accommodate thousands, enabling a vast network of agents to execute tasks safely.

“This could set a standard for any application needing coordinated agents, such as warehouse robots, search-and-rescue drones, and self-driving cars,” explains Chuchu Fan, associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT. “Our method acts as a protective layer, allowing each agent to focus on its mission while we determine how to maintain safety.”

The findings from this research are detailed in a study that appears this month in the journal IEEE Transactions on Robotics. Co-authors include MIT graduate students Songyuan Zhang and Oswin So, along with Kunal Garg, a former postdoc at MIT who is now an assistant professor at Arizona State University.

Challenges of Safety Margins

When engineers design safety protocols for multiagent systems, they typically need to account for the potential motions of each agent in relation to the others, making this pairwise path-planning both time-consuming and computationally intensive. Even with meticulous planning, safety isn’t always assured.

In a standard drone show setting, each drone follows a defined trajectory, almost “closing their eyes” as they execute their flight plan. “They only know their destination and timing, leaving little room for unexpected events,” notes Zhang, the lead author of the study.

In response, the MIT team focused on developing a training method for a smaller number of agents that could be effectively scaled to larger groups without compromising safety. Their approach directs agents to continuously assess their safety boundaries, allowing them flexibility in path selection as long as they remain within those boundaries. This mirrors human navigation in crowded environments.

“Consider navigating a busy shopping mall,” So compares. “You only focus on the immediate vicinity, say within five meters around you, for safe movements and avoiding collisions. Our approach adopts this localized strategy.”

Introducing GCBF+

The team introduces GCBF+, short for “Graph Control Barrier Function.” This mathematical framework calculates safety barriers that dynamically adjust as agents move amidst others in the system. By analyzing just a small number of agents, the MIT team can derive safety zones that effectively represent a larger group’s dynamics.

This method enables them to efficiently “copy-paste” these calculated barrier functions to each agent, establishing a comprehensive map of safety zones for any number of agents.

In their method, an agent’s “sensing radius” plays a crucial role, involving the observable environment based on the agent’s sensor capabilities. In line with the shopping mall analogy, agents prioritize avoiding collisions with others within their sensing reach.

Using computer models to represent the agents’ physical traits and limitations, the researchers simulate how multiple agents travel along predetermined paths, tracking potential interactions and collisions. “From these simulations, we generate laws to minimize safety violations and refine the control system for enhanced safety,” explains Zhang.

Ultimately, this allows the programmed agents to adaptively map their safety zones in real time based on observed movements of nearby agents, maintaining a reactive planning capability.

“Our controller doesn’t rely on preplanned routes. Instead, it dynamically responds to real-time data about agent positions and velocities, continuously adjusting plans as circumstances evolve,” adds Fan.

The team successfully demonstrated GCBF+ with eight lightweight Crazyflies—small quadrotor drones tasked with midair positioning shifts. Without GCBF+, the drones would collide if they followed direct paths. However, after their training, they adeptly navigated around each other, ensuring safe position changes.

In another test, Crazyflies executed landings on moving Turtlebots, successfully avoiding collisions in the process. “With our framework, the drones need only be given destination points instead of complete trajectories. They autonomously navigate to their goals without colliding,” Fan envisions, expressing the method’s potential applicability across various multiagent systems, including drone shows, warehouse operations, autonomous vehicles, and delivery services.

This research received partial support from the U.S. National Science Foundation, MIT Lincoln Laboratory under the Safety in Aerobatic Flight Regimes (SAFR) program, and the Defence Science and Technology Agency of Singapore.

Photo credit & article inspired by: Massachusetts Institute of Technology