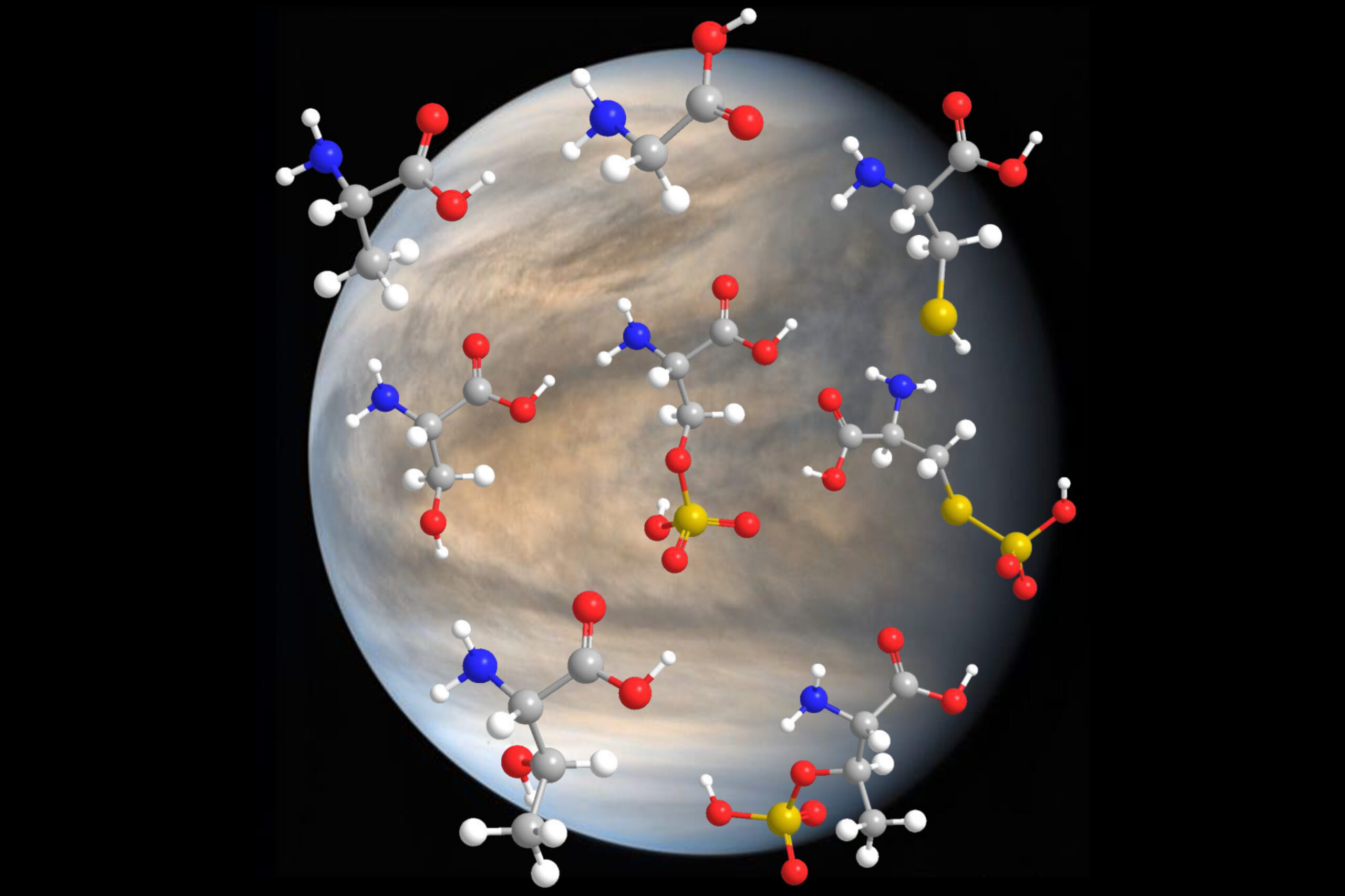

Could there be life beyond Earth in our solar system? Scientists are looking towards the clouds of Venus as a potential habitat. Unlike the hostile surface conditions of Venus, its cloud layer, situated 30 to 40 miles above ground, offers more temperate climates, which may support extreme forms of life.

Traditionally, researchers believed that any organisms thriving in the Venusian atmosphere would differ significantly from terrestrial life. This assumption stems from the fact that the clouds in Venus are composed of highly toxic sulfuric acid droplets—an aggressive chemical known for its ability to dissolve metals and obliterate most biological molecules found on Earth.

However, a groundbreaking study by MIT researchers is challenging this long-held belief. In a paper published today in the journal Astrobiology, they reveal that several fundamental building blocks of life can actually remain stable in concentrated sulfuric acid solutions.

The researchers identified that 19 essential amino acids can maintain their stability for up to four weeks when subjected to conditions resembling those in Venus’ clouds. Notably, the core structure (or “backbone”) of all 19 amino acids stayed intact in sulfuric acid concentrations ranging from 81% to 98%.

“What’s truly surprising is that concentrated sulfuric acid may not be as hostile to organic chemistry as we assumed,” comments Janusz Petkowski, one of the study’s co-authors and a research affiliate in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) at MIT.

Study author Sara Seager, MIT’s Class of 1941 Professor of Planetary Sciences and a member of the Physics and Aeronautics and Astronautics departments, adds, “Our findings suggest the possibility that the clouds of Venus could host complicated chemicals necessary for life. While the evolution of life there would likely be drastically different from Earth, this work opens up exciting possibilities.”

The team includes Maxwell Seager, an undergraduate at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and William Bains, a research affiliate at MIT and a scientist at Cardiff University.

Exploring Life’s Building Blocks in Acid

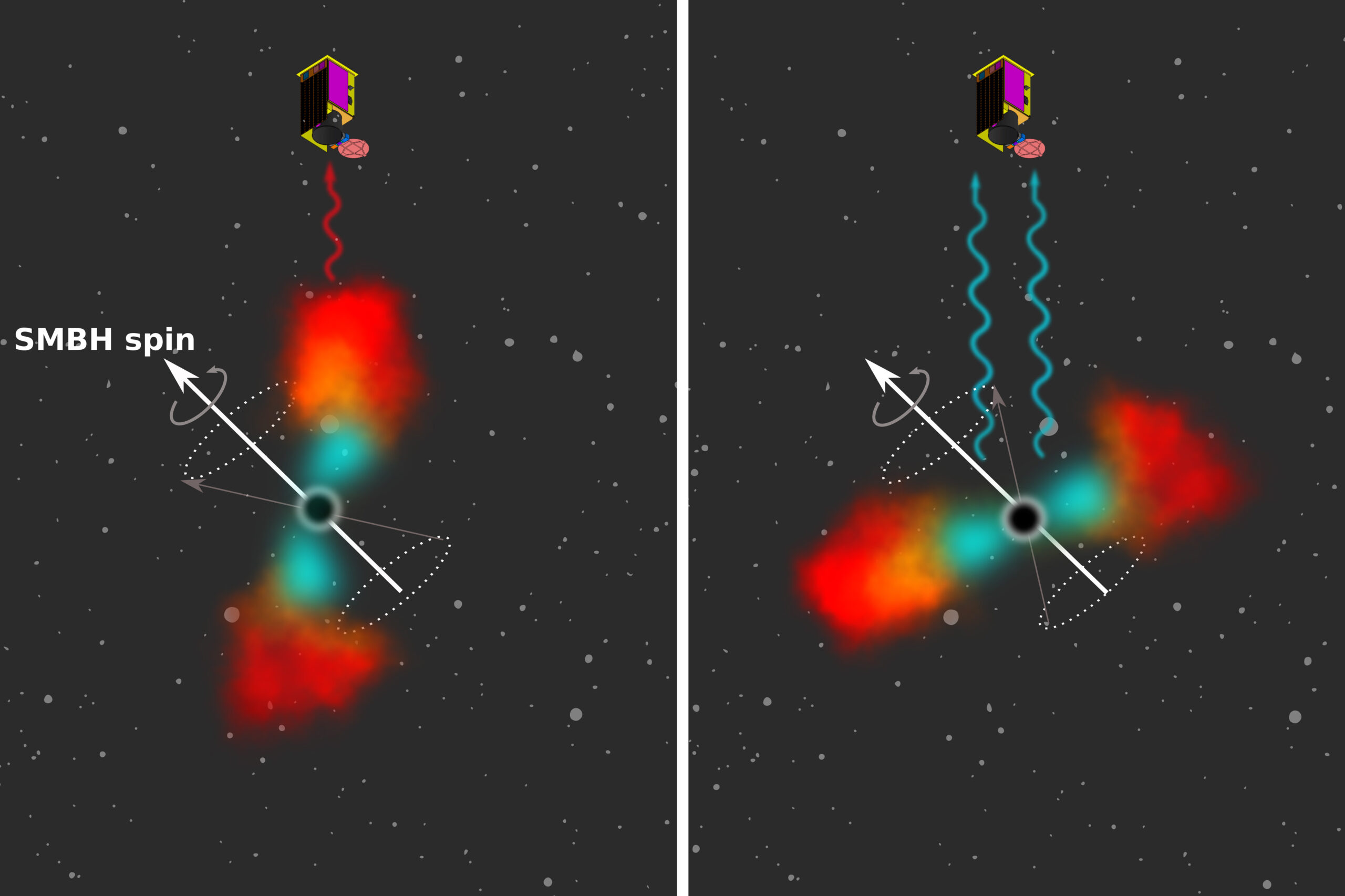

The quest for life in the clouds of Venus has been invigorated in recent years, particularly following a controversial detection of phosphine—an organic molecule often associated with biological processes—in the planet’s atmosphere. While this finding is still under scrutiny, it has reignited interest in whether Earth’s sister planet could actually harbor life.

In pursuit of answers, scientists are preparing to launch multiple missions to Venus, including a privately funded venture led by Rocket Lab, a California-based launch company. This mission, with Seager as the principal investigator, aims to send a spacecraft to traverse the clouds, analyzing their chemical makeup for signs of organic constituents.

As the mission prepares for a January 2025 launch, Seager and her team have been experimenting with different molecules in concentrated sulfuric acid to determine which components of terrestrial life might also be stable in the extreme conditions of Venus’ atmosphere, which are believed to be far more acidic than the most extreme environments on Earth.

“Many people think that concentrated sulfuric acid acts as a relentless solvent that destroys everything,” Petkowski remarks. “We are demonstrating that this is not necessarily the case.”

The research team has previously shown that complex organic molecules—including certain fatty acids and nucleic acids—exhibit remarkable stability in sulfuric acid. They emphasize that while complex organic chemistry is not synonymous with life, it is a prerequisite for its existence.

So, if certain molecules can endure in sulfuric acid, could it be that the acidic clouds of Venus provide a hospitable environment for life, even if it is not currently inhabited?

In the latest research, the scientists focused on amino acids—vital components that combine to form essential proteins, each serving a specific role in sustaining life. All living organisms on Earth require amino acids to create proteins necessary for various life-sustaining functions, such as metabolizing food, generating energy, building muscle, and repairing tissue.

“When considering the four key building blocks of life—nucleic acids, amino acids, fatty acids, and carbohydrates—we have established that some fatty acids can form micelles and vesicles in sulfuric acid, while nucleic acid bases remain stable in these harsh conditions. Carbohydrates, on the other hand, have proven to be highly reactive in sulfuric acid,” explains Maxwell Seager. “This left us focusing on amino acids as the final major component to investigate.”

A Backbone That Holds Strong

The scientists embarked on their sulfuric acid studies during the pandemic, conducting experiments from a home laboratory. In early 2023, they procured powdered samples of 20 biogenic amino acids, fundamental to life on Earth. Dissolving these samples in sulfuric acid mixed with water at concentrations of 81% and 98%, reflecting conditions within Venus’ clouds, they set up their experimental observatory.

After allowing the mixtures to incubate for a day, the samples were then analyzed at MIT’s Department of Chemistry Instrumentation Facility (DCIF) using a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer. Over the course of four weeks, the research team assessed the samples repeatedly and found that the core structure of 19 out of the 20 amino acids remained stable and unchanged, even under highly acidic conditions.

“Demonstrating that the backbone of these amino acids endures in sulfuric acid doesn’t confirm there is life on Venus,” says Maxwell Seager. “However, if we had found that this backbone was altered, it would have significantly diminished the chances of life as we know it.”

“Now, with the discovery of numerous stable amino acids and nucleic acids in 98% sulfuric acid, the prospect of life surviving in such environments may not seem as far-fetched as it once did,” remarks Sanjay Limaye, a planetary scientist at the University of Wisconsin with over 45 years of experience studying Venus, who was not involved in the study. “Certainly, many challenges remain, but life designed for water and adapted to sulfuric acid shouldn’t be quickly dismissed.”

The research team recognizes that the chemical environment of Venus’ clouds is likely more complicated than their controlled lab conditions. They plan to factor in additional trace gases in future experiments to better simulate the atmospheric conditions of Venus.

“There aren’t many research groups examining chemistry in sulfuric acid, and consensus is hard to come by,” adds Sara Seager. “We are simply thrilled that this recent finding adds one more ‘yes’ to the ongoing exploration of the possibility of life on Venus.”

Photo credit & article inspired by: Massachusetts Institute of Technology