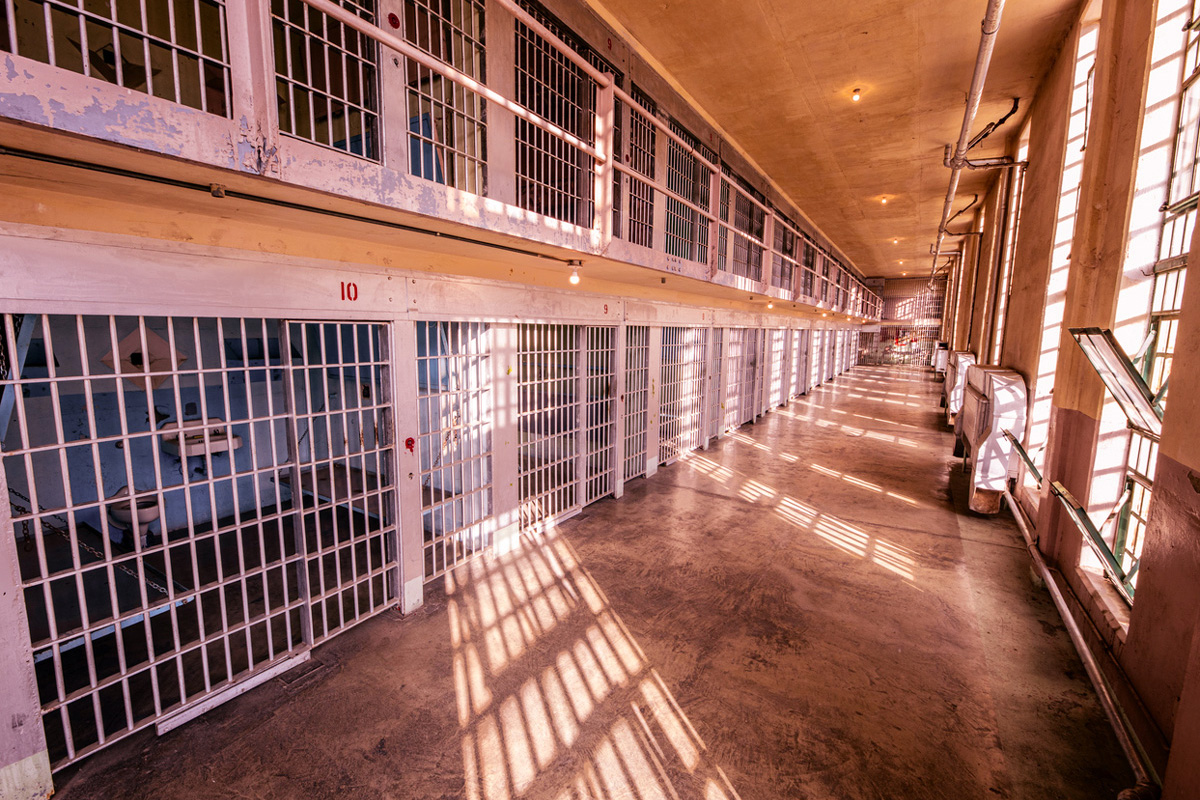

As summer temperatures rise, so does the risk of heat-related illnesses and fatalities. While most people can mitigate their heat exposure by simply opening a window, increasing air conditioning, or drinking water, those incarcerated often lack such freedom. This makes prison populations particularly susceptible to heat-related issues due to their confinement conditions.

A recent study from MIT researchers investigates the effect of summertime heat exposure in U.S. prisons and pinpoints specific facility characteristics that may heighten prisoners’ vulnerability during extreme heat events.

Using high-resolution air temperature data, the researchers evaluated daily average outdoor temperatures for 1,614 prisons across the nation from 1990 to 2023. Their findings indicate that the highest heat exposure typically occurs in prisons located in the Southwestern U.S. Meanwhile, facilities experiencing the most significant increases in summertime heat are found in the Pacific Northwest, Northeast, and parts of the Midwest.

These findings are not limited to prisons; any community or facility in similar geographic areas faces comparable environmental challenges. However, the research delves into prison-specific factors that can increase heat exposure risks for inmates. The authors identified nine critical characteristics associated with heightened vulnerability, including restricted movement, inadequate staffing, and insufficient mental health services. Individuals residing or working in prisons with any of these traits may face compounded heat risks.

Moreover, the study examined the demographics of 1,260 prisons, revealing that facilities with higher average heat exposures also tend to have larger non-white and Hispanic populations. Published in the journal GeoHealth, this research equips policymakers and community leaders with essential insights to assess and tackle the heat risks faced by incarcerated individuals, which are expected to intensify with climate change.

“This issue is not solely about climate change, but it is increasingly exacerbated by it,” explains lead author Ufuoma Ovienmhada SM ’20, PhD ’24, from the MIT Media Lab. “Many prisons were never constructed to be comfortable or humane. Climate change merely amplifies the challenges faced by these facilities in allowing incarcerated individuals to manage their own heat exposure.”

Co-authors of the study include Danielle Wood, an associate professor at MIT specializing in media arts and sciences and AeroAstro, as well as Brent Minchew, an associate professor of geophysics at the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. Additionally, the team included Ahmed Diongue ’24, Mia Hines-Shanks from Grinnell College, and Michael Krisch from Columbia University.

Exploring Environmental Justice

This study extends ongoing initiatives at the Media Lab, where Wood heads the Space Enabled research group, dedicated to promoting social and environmental justice through satellite data and advanced technologies.

The impetus for researching prison heat exposure originated in 2020 when Ovienmhada, as co-president of MIT’s Black Graduate Student Union, became involved in community organization efforts following George Floyd’s murder by the Minneapolis police.

“We began to engage more on campus regarding policing and reimagining public safety. This led me to discover the intersections between prison systems and environmental risks,” Ovienmhada shares, emphasizing her commitment to mapping out various environmental challenges faced by incarceration facilities. “Extreme heat poses severe threats for incarcerated individuals.”

The research team utilized a comprehensive database from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, which lists the locations and boundaries of carceral facilities across the U.S. From over 6,000 prisons, jails, and detention centers, they focused on 1,614 prisons, which house nearly 1.4 million individuals and employ approximately 337,000 staff.

They accessed Daymet, a detailed weather and climate database that tracks daily temperatures across the United States at a 1-kilometer resolution. For each of the 1,614 prison locations, they documented the daily outdoor temperatures for every summer from 1990 to 2023, noting that the majority of current state and federal correctional facilities were constructed by 1990.

Additionally, the researchers examined U.S. Census data to analyze facility demographics and specific characteristics that could affect conditions within prisons. They acknowledged a limitation in their study regarding the lack of available information concerning climate control systems in these facilities.

“There isn’t a comprehensive resource available to determine if a facility has air conditioning,” Ovienmhada points out. “Even in prisons that do have AC, incarcerated individuals may not have regular access to these cooling systems,” suggesting that their outdoor air temperature measurements closely reflect the reality of conditions within.

Factors Influencing Heat Exposure

The researchers uncovered that more than 98% of U.S. prisons experienced at least 10 days of summer heat hotter than any previous recorded average for their location. The analysis revealed that the highest heat-exposed facilities are predominantly situated in the Southwestern U.S., a region where no universal air conditioning regulations exist for state-operated prisons, with the exception of New Mexico.

“States independently manage their prison systems, resulting in a lack of uniform data collection and air conditioning policies,” Wood notes. While some states do offer information regarding cooling systems in specific prisons, overall data remains sparse and inconsistent, hindering comprehensive national assessments.

Although the researchers did not capture direct air conditioning data, they did investigate other facility-level factors that might worsen heat-related health impacts. Drawing from scientific literature, they identified 17 measurable conditions contributing to heat-related issues, including overcrowding and insufficient staffing.

“We understand that when a space is overcrowded, it can feel hotter inside, even with air conditioning,” Ovienmhada explains. “Staffing levels play a vital role as well. Facilities lacking air conditioning that still attempt to mitigate heat risks may rely on staff to distribute ice or water throughout the day. In understaffed or neglectful environments, inmates are likely to be more vulnerable to extreme heat.”

The study determined that prisons exhibiting any of nine identified variables faced statistically significant higher heat exposures than those without. If a prison has one of these nine factors, it can dramatically increase inmates’ heat risks by combining high heat exposure with other vulnerabilities. Identifying these variables could aid state regulators and advocates in prioritizing prisons for heat mitigation interventions.

“As the prison population ages, and even for states not typically associated with high temperatures, there exists a responsibility to respond,” Wood stresses. “For example, the Northwest, an area often viewed as temperate, has recorded increasing heat risks in recent years. A few days of extreme heat each year can be hazardous, especially for a population with limited ability to manage their exposure.”

This research was supported by NASA, the MIT Media Lab, and MIT’s Institute for Data, Systems, and Society’s Research Initiative on Combatting Systemic Racism.

Photo credit & article inspired by: Massachusetts Institute of Technology