For many generations, Andrew Sutherland’s family had a cherished calling: playing the bagpipes. Growing up in Halifax, Nova Scotia, he was surrounded by a lineage steeped in Scottish tradition, where his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather all competed in bagpiping across North America. Even his aunts and uncles participated in this family passion.

However, Andrew took a different path. Instead of following the family tradition, he found his passion in mathematics. After completing his education, he entered a PhD program and ultimately became a professor at the esteemed MIT Sloan School of Management. Sutherland is a dynamic scholar whose research encompasses financing, auditing practices within private firms, the impacts of financial technology, and methods for detecting business fraud.

“I was actually the first male in my family not to pick up the bagpipes, and the first to attend university,” Sutherland jokes. “I suppose in a way, I’m the family’s black sheep for not continuing the tradition.”

While the bagpipe legacy may have faded, Sutherland’s contributions to MIT are invaluable. His expertise in accounting has opened new doors to understanding broader business practices.

“Much of what we understand about the financial system and corporate performance comes from large public companies,” Sutherland notes. “Yet, in the U.S., private firms are responsible for generating over half of all employment and investments. Until recently, we lacked comprehensive insights into their capital acquisition and decision-making processes.”

Thanks to his innovative research and teaching methods, Sutherland was awarded tenure at MIT last year.

A Uniquely Different Path

Sutherland takes pride in his family’s rich heritage; his grandfather and great-grandfather educated many successful bagpipers in Nova Scotia. Still, Sutherland gravitated towards business studies, earning his undergraduate degree in commerce with honors in accounting from York University in Toronto, followed by an MBA from Carnegie Mellon University, specializing in finance and quantitative analysis.

His desire to delve into financial markets fueled his curiosity about how banks assess and lend to private businesses. He entered the PhD program at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, where he was encouraged to pursue these significant questions by notable scholars like Christian Leuz and Douglas Diamond, now a Nobel Prize laureate.

Sutherland earned his PhD in 2015, producing a dissertation on the evolving dynamics of banker-to-business relationships, published in 2018. This research explored how transparency-enhancing technologies were transforming the credit acquisition process for small businesses.

“Two decades ago, banking relied heavily on personal relationships,” Sutherland explains. “You might engage socially with your loan officer. Today, the landscape has shifted dramatically due to technology. Many lending processes now occur online, eliminating the need for traditional audited financial statements.” This transformation has transitioned credit markets from being relationship-centric to transactional.

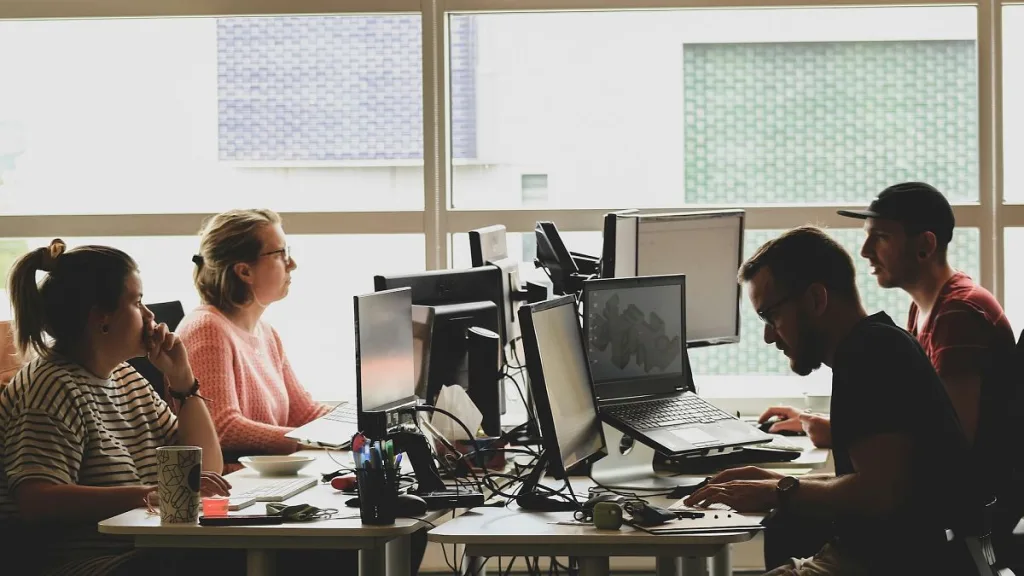

Now serving as an associate professor at MIT, Sutherland has remained with the Institute since joining the faculty in 2015. His office at MIT Sloan, adorned with modern art, including an Andy Warhol print, reflects his appreciation for creativity coupled with academia.

Sutherland has collaborated on five research papers with Michael Minnis, now a deputy dean at Chicago Booth, revealing the varied practices in lending and contract negotiations in the small business realm. In one pivotal 2017 study, they discovered that banks were less likely to gather verified financial statements from construction companies prior to the 2008 housing crisis, highlighting the lax lending practices of that era. Another study revealed that banks with deep industry knowledge tended to trust “soft” information more than “hard” data when approving loans.

“We’re striving to understand the ‘Wild West’ of accounting and finance, especially concerning entrepreneurs and privately held companies that can maneuver with fewer regulations,” Sutherland elaborates. “We seek to understand the choices these firms make and the economic theories that underpin these decisions.”

Understanding Trust and Fraud in Finance

Sutherland’s research often focuses on trust, regulations, and the potential for financial misconduct—topics that resonate strongly with his students.

In a groundbreaking 2020 study published in the Journal of Financial Economics, Sutherland and his co-authors demonstrated that a 2010 modification to the investment adviser qualification exam, which shifted focus away from ethics, led to troubling outcomes: Those who passed the exam under the previous standards were 25% less likely to engage in misconduct.

“This research indicates a clear correlation between ethics training and professional behavior,” Sutherland notes. “We can even use employee turnover as a potential red flag for fraud—those trained in ethics often leave before their companies’ scandals unfold.”

The Role of Teaching at MIT

At MIT Sloan, Sutherland’s research aligns well with the entrepreneurial spirit of many students eager to launch startups.

“Sloan attracts a wealth of aspiring entrepreneurs,” he observes. “They’re naturally curious about financing options: Should they approach a bank? Seek equity? How do they stack up against competitors? While large public firms often have textbook answers to these questions, private firms remain an enigma, motivating me to find solutions.”

Although Sutherland is a prolific researcher, he emphasizes the importance of engaging students in the classroom.

“My goal with each project is to translate the findings into classroom discussions that resonate with students,” Sutherland expresses with enthusiasm.

Despite departing from the family’s bagpiping legacy, Sutherland still thrives in a performing role as an educator. When discussing his students, he radiates positivity.

“One of the greatest joys of teaching at MIT,” he shares, “is the caliber of my students. They’re sharp enough to challenge my research and engage in deep discussions. It’s truly the best environment to teach in because of their inquisitive and intelligent nature.”

Photo credit & article inspired by: Massachusetts Institute of Technology