As climate change continues to threaten coastal regions, images of homes being swept away by storm surges and eroding shorelines have become increasingly common. In 2022 alone, coastal storms in the U.S. resulted in staggering losses of $165 billion. However, a new study from MIT offers a glimmer of hope: protecting and enhancing salt marshes in front of seawalls may effectively safeguard coastlines while being economically viable.

This groundbreaking research appears in the journal Communications Earth and Environment and is authored by MIT graduate student Ernie I. H. Lee and civil and environmental engineering professor Heidi Nepf. Professor Nepf stresses the importance of this study by stating that restoring coastal marshes is not just a nice-to-have, but is, in fact, a financially justifiable action. The findings highlight how the wave-reducing properties of salt marshes allow for the construction of shorter seawalls, thus lowering overall development costs while maintaining storm protection.

One of the most significant revelations from the study, according to Nepf, is that even relatively small salt marshes, just tens of meters in width, can offer substantial protective benefits. This insight is particularly encouraging for urban planners who may have previously dismissed the restoration of small marshes as unfeasible. “We demonstrate that these smaller marshes can make a considerable difference financially,” she adds.

Previous research has highlighted the advantages of extensive marshes in flood mitigation, but Lee points out that such studies typically focused on larger landscapes, often hundreds of meters wide. “Our study aims to show that the benefits hold true even in urban settings where real estate pressures limit available marshland,” he notes, particularly in regions already equipped with seawalls.

The team utilized advanced computer simulations to model how waves behave over various shore profiles, examining the morphology of different salt marsh plants—such as their height, stiffness, and density—rather than relying solely on empirical drag coefficients. Nepf explains, “This physically based model enables us to analyze the interplay between plant species and wave dynamics across different seasons without extensive field measurements.”

For their benefit-cost analysis, the researchers utilized a straightforward measure: determining how much shorter a seawall could be if it were supplemented by a specific size of marsh. Unlike traditional methods that measure asset value and flood risk, which can be quite variable, they opted for a more direct assessment—the equivalent height of seawall necessary to ensure similar storm protection.

The study compared various plant models, revealing a twofold difference in their efficacy in wave attenuation, with all types providing valuable benefits. To illustrate their findings, Nepf and Lee analyzed local salt marshes in Salem, Massachusetts, where restoration projects are currently in progress. Their model predicts that a healthy salt marsh could offset the need for an additional seawall height of 1.7 meters (approximately 5.5 feet), enough to ensure pedestrian safety against wave overtopping.

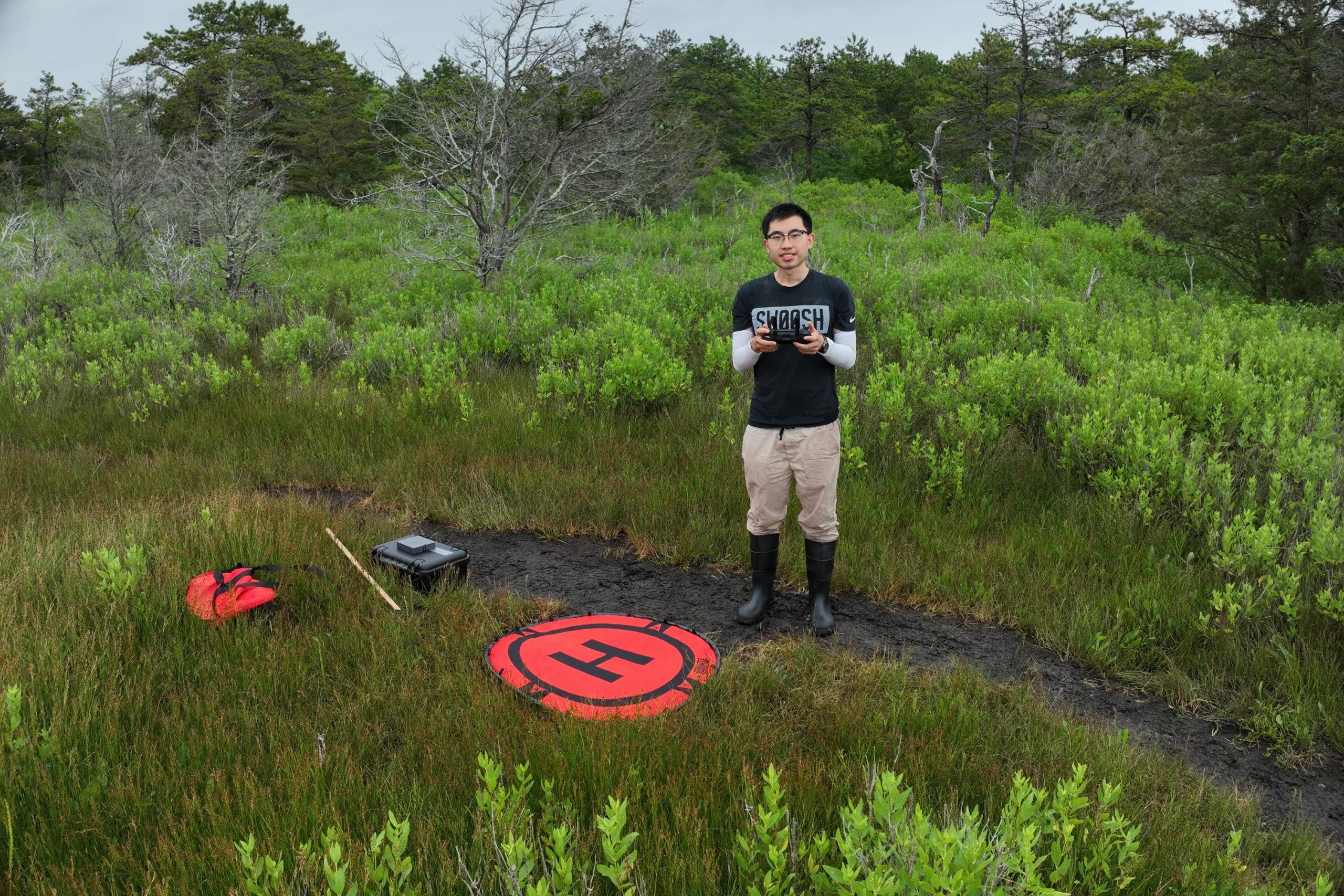

Collecting the necessary real-world data for modeling marshes, such as maps of species distribution, plant heights, and shoot density, has proven to be quite labor-intensive. In response, Lee is developing a method that combines drone imaging with machine learning to streamline this mapping process. Nepf highlights the importance of this tool, stating, “It will empower researchers to evaluate marshland areas and determine their flood mitigation worth.”

Recently, the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs issued guidelines for quantifying ecosystem service value in federal project planning. Nepf points out that while these guidelines exist, they often lack specific quantitative methods. “Our study addresses that gap,” she emphasizes.

Moreover, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s benefit-cost analysis toolkit provides guidelines for quantifying environmental services. Lee notes, “A key innovation of our research is its ability to quantify the protective value of marshes, offering policymakers a valuable resource for understanding these ecosystem services.”

For environmental engineers, the team has made their modeling software freely available online via GitHub, providing a user-friendly, one-dimensional model that standard consulting firms can easily access.

Xioaxia Zhang, an expert in environmental science at Shenzen University, remarked, “This paper offers a practical tool for translating the wave attenuation capabilities of marshes into economic values, empowering decision-makers to adopt marshes as nature-based coastal defenses.” He concludes that the results demonstrate salt marshes are both ecologically and financially beneficial.

“This study represents a pivotal step toward quantifying marshes’ protective values,” states Bas Borsje, an associate professor specializing in nature-based flood protection at the University of Twente. “The pressing need now is translating these findings into actionable strategies for decision-makers. This research stands out because it equips them with concrete information on salt marsh protection value.”

Lee’s research received funding from the Schoettler Scholarship Fund through the MIT Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Photo credit & article inspired by: Massachusetts Institute of Technology